Lecturing has been the traditional method for subject-matter experts to get content across to their audience. However, research shows that lecturing isn’t the most effective method for helping the audience retain content.

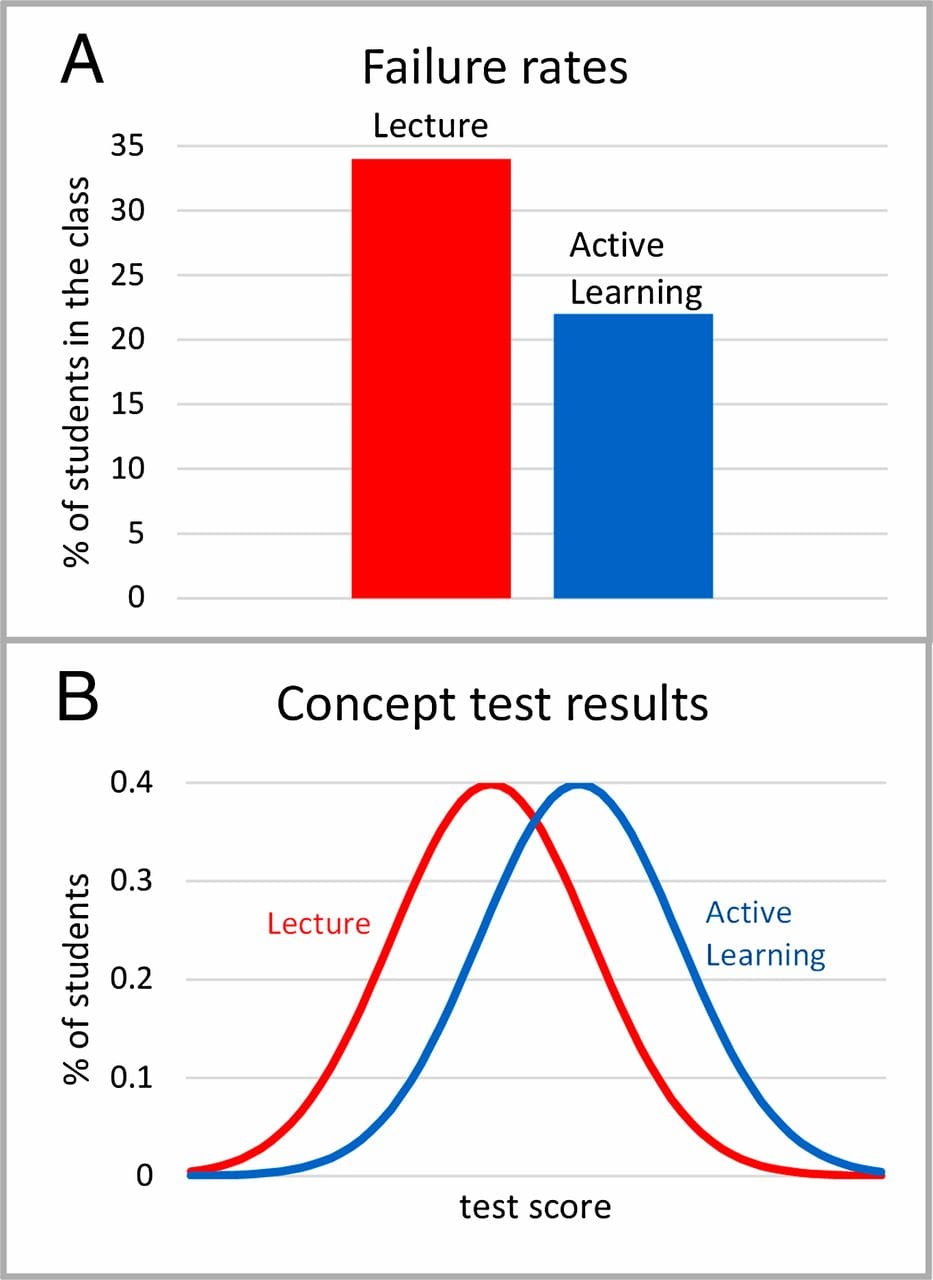

According to research by Freeman S, et al. when using active learning compared to traditional lecture students’ average failure rate decreased by 12% and performance on identical or comparable tests improved by nearly half of the standard deviation of the test scores (an effect size of 0.47).

"Fig. 1. Comparisons of average results for studies reported in ref. 3. (A) Failure rates for the active learning courses and the lecture courses. (B) Shift in distribution of student scores on concept inventory tests." (Weiman, 2014).

Escaping the lecture trap

It’s easy to fall into lecture-style approaches because they are familiar. However, in lecture-style courses, there is often a big gap between the instructor’s perception of what students are retaining and what they are actually learning and understanding.

While the instructor may feel like he/she has delivered the most important information, it isn’t always clear exactly what the student has comprehended (or even misunderstood!) from the lecture. That’s the lecture trap. It’s easy to feel students are learning everything because you have said everything they need to learn.

Professor Sara Collina of Georgetown University accounted to us her experience planning and delivering lectures, “I would lecture on what I thought were the most important issues and concepts that I believe my students “should” know. But it was a show; I was working harder than my students, and getting burnt out.”

By their very design, interactive teaching strategies remove the veil between what an instructor is teaching and what students are learning because they allow instructors to get real-time insights on their class’s progress.

While there can be an upfront time investment to make these changes, overall, these strategies help instructors to teach more effectively without requiring much more time. Instructors do this by targeting the specific needs of the students sitting in front of them instead of preparing a complete summary of that week's readings or textbook topics.

Before adding in interactive moments for students, we have found it is helpful to do a bit of thinking on your goals and structure for your lecture.

Step 1: Adjust your goals for class time and be clear about those goals with your students

This adjustment is less about your role as an expert and more about shifting the mindset of the class. We like to think of in-class time as an opportunity to have students discover information for themselves.

In this type of environment, your expertise in the course’s subject matter takes on a more strategic benefit: using class-time to evaluate students’ needs at that time and in regards to the current subject matter. With this knowledge, you can tailor the information that you deliver in class and students will gain a deeper understanding of the material.

Step 2: Break your lectures into 15 to 20 minutes mini-lectures

The research tells us that young adults can recall only 3 or 4 longer verbal chunks, such as idioms or short sentences (Gilchrist, Cowan, & Naveh-Benjamin, 2008). Why we have this storage limit is still unclear, but experts typically fall in two camps (1) capacity limits as weaknesses, and (2) capacity limits as strengths (Cowan, 2010). (For a more detailed explanation of each of these views, check out Cowan's research.

Nelson Cowan (2010), provides a great example of what this limit looks like in the classroom. “During essay comprehension a student might need to hold in mind concurrently the major premise, the point made in the previous paragraph, and a fact and an opinion presented in the current paragraph. Only when all of these elements have been integrated into a single chunk can the reader successfully continue to read and understand. Forgetting one of these ideas may lead to a more shallow understanding of the text, or to the need to go back and re-read.”

We believe that breaking up your lectures into “content bursts” or “mini lectures” allow the space for student interaction and processing ideas. We have seen success when professors do mini-lectures on key concepts that would be difficult for students to research on their own.

Step 3: Add student interaction and inquiry in between your mini-lectures

Moments of student interaction can provide you with actionable feedback on what students understood from your content burst as well as to help you identify which topics you will want to follow up on or reapproach. Students benefit from peer interactions that allow them to practice applying their new concepts and skills in real time.

As a bonus, you’ll see an immediate increase in student engagement as peers talk through course topics in the safety of a partnership or small group--a much lower social risk than speaking in front of the whole class.

By listening and observing during these interactive moments, you’ll have a clear understanding of where your students and what to teach next. You’ll be able to frame your mini-lectures based on what you observe about your students as they actively learn.

There are lots of ways to get students interacting with your lectures!

- Prompt students to write a question about their most confusing point from the readings. Gather all the questions they have before class, and address three of the most popular or common groups of questions to kick the next class off.

- After you complete your module, pair students, and have them share their curiosities and Natural Next Questions from the module.

- Then, include students’ ideas in your next mini-lecture. Start with what they think is more important to show you’re listening.

- Record all your video lectures, have them listen outside of class, and use class to do problems.

Use class time for discussion

Ask students to decide on the most important things to discuss

Break your students into groups to discuss

Have your students ask questions about their muddiest points

You may have noticed that we didn’t mention clickers, polling or gamification. While these can be engaging tools, they only support interactive learning if they are used authentically to highlight what is relevant and valuable to students’ learning. At first, these tools may seem shiny and entertaining, but if they are not used to surface learning needs that you can respond to, students will quickly dismiss them as not having a value.

Pro Tip: Align your assessments

By aligning your assessments with your interactive lecture strategies, you will keep students motivated and feeling like they are getting the most value out of class.

Use student questions and discussions in class to drive your quizzes and essays. Be sure to let students know that you are incorporating their questions and opinions from class-time. We have seen engagement increase when students feel that their voice and perspective matters.

Final thoughts

Lecture has been the predominant teaching style for hundreds of years, even in the face of research identifying the limits on a young adult’s working memory. By reformatting your teaching to include more interactive learning strategies, you will have the double benefit of lifting student engagement and being able to tailor your approaches to the unique group of students in your course.

References:

Carl E. Wieman (2014) Large-scale comparison of science teaching methods sends clear message. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Jun 2014, 111 (23) 8319-8320; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1407304111

Freeman S, et al. (2014) Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:8410–8415.

Gilchrist, A. L., Cowan, N., & Naveh-Benjamin, M. (2008). Working memory capacity for spoken sentences decreases with adult ageing: recall of fewer but not smaller chunks in older adults. Memory (Hove, England), 16(7), 773–787. doi:10.1080/09658210802261124

Cowan N. (2010). The Magical Mystery Four: How is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why?. Current directions in psychological science, 19(1), 51–57. doi:10.1177/0963721409359277