“Oh yeah, you’re the ones helping teachers ask questions!” exclaimed our new friend at a conference…but no, we’re actually the ones helping students ask questions.

This is such a common idea – teachers ask questions, everyone knows that, ask Socrates! But we think the secret to learning, the secret to progress, the secret to leading, is for the learner to ask great questions. Questions drive us forward.

Without the right question, we’ll never ever get to the right answer.

Content Questions and Natural Next Questions

In the attempts of our team to understand the process of learning, we have observed that student questions fall into two main categories:

- those to clarify a specific piece of content

- those that push the class forward towards a solution to a larger identified goal or problem.

We’re all trained to ask questions about something we just learned. Content questions are the usual. We get asked content questions on exams, and we ask them during class. At the bottom of this post you can see the peer-reviewed research on these types of questions.

But the far more interesting, the far more powerful kind of question is the one that takes us a step away from our current knowledge and toward our greater goal: we call that second kind of question a Natural Next Question.

(By the way, is it really true that there’s no such thing as a stupid question, or a bad question? Here’s a way to think about what a lazy question is!)

Three Metrics That Help Continuously Improve Questions

And because we think the Natural Next Question is such a key concept, and that it unlocks the right path to solutions in every part of life, we’ve gone a step further: We’re creating the Question Productivity Index, a way to actually score the productivity of questions, and to practice asking better and better ones.

We studied 800 Natural Next Questions from students who had taken our classes, and we came up with three metrics for what makes such a question a really good one:

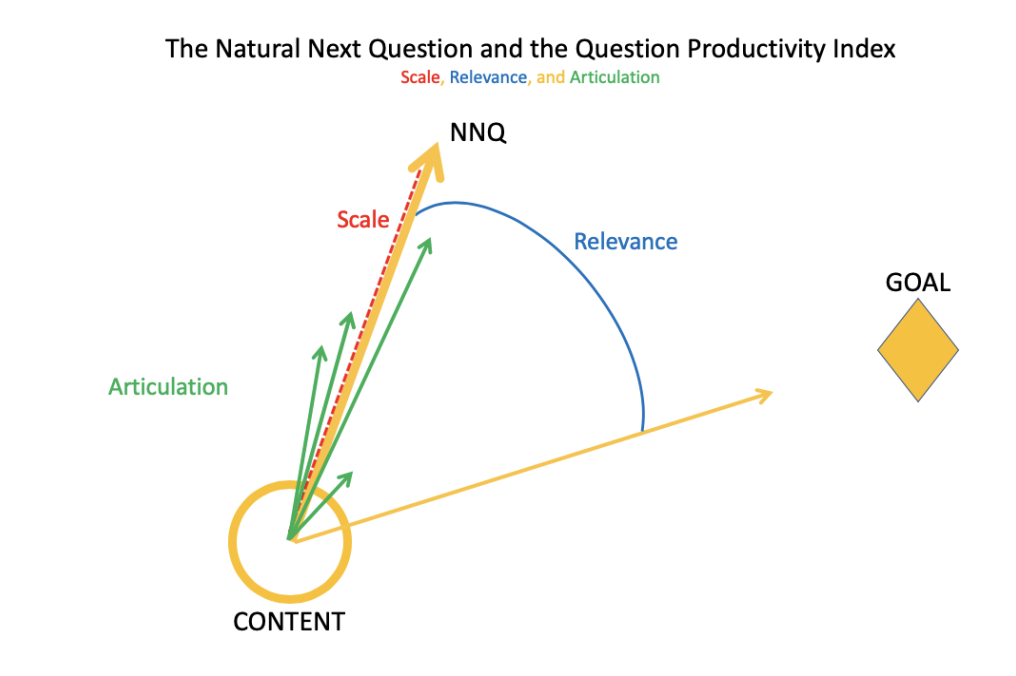

- Relevance: How relevant the question is to the larger learning goal of the class.

- Scale: The degree to which the question takes the class one reasonable step from their currently knowledge level to solving the key problem, without needing to be broken into smaller questions.

- Articulation: The degree to which the question is well-posed: not too vague, not poorly worded. Would everyone in the group agree on what this question means?

Graphically, scale, articulation, and relevance can be seen in this figure, as the size of the step toward the bigger goal (scale, the length of the question’s vector), how clearly everyone in the group understands the question (articulation),and how directly this question aims at the bigger goal (relevance, the direction of the question’s vector).

Our Journey

For four years now we’ve been experimenting with classes where the students’ Natural Next Questions guide the whole direction of learning. These classes are thrilling – but we know it’s a big, big step to take. We’ve found we can help students learn to ask better questions with just the concept of the Natural Next Question, and maybe our new Question Productivity Index.

In the last three courses we taught this way, we had students ask their Natural Next Questions for a few weeks, and then we introduced them to the Question Productivity Index. Each week we’d ask the students to score their own questions, and see if they could edit the questions to be better. Students began speaking to each other in Question Productivity Index-speak: “I’d give that question an 8-5-7. What do you think?” Their questions got more productive, and their research moved ahead, and they gained confidence and resilience in trying to make a new step each week. Just what we all need in life.

Here’s the question rubric we hand out to our students. You might want to try asking your students to ask questions – they can practice outside of class, even write them on index cards and hand them in. It’s such an easy first step to engage learners in the content. And then, you can show them that questions can be even better, even more productive.

Getting Started

We’ve seen great student learning outcomes when instructors connect student use of Natural Next Questions to a project outcome or goal. For example, instructors often have students practice asking Natural Next Questions to help them achieve a higher quality final paper, presentation, or work product by first asking students to iteratively improve their research question based on Question Productivity Index (QPI) ratings.

Below is an exercise to have students repeatedly dig into their research topic before starting on their final project so that their work is well informed, and they've had a chance to learn about the nuance and complexity of their subject. You can have students do this in groups or individually.

Setup

- Instructor sets goals and requirements for the final paper, presentation, or work product

- If applicable, instructor assigns students to their groups

- Students complete pre-work (e.g., weekly readings, initial research, attends class, etc.)

Exercise Flow

- Students are instructed: “Based on what you saw in the pre-work, write your natural next question that will help you get a step closer to your research goal.”

- Each student writes their Natural Next Questions

- Students are paired and score their partners’ question with QPI rubric

- Alternative: Students self-rate their question with the QPI rubric to improve it

- Students review the feedback from their partners

- Alternative: Students reflect on their scores and discuss as a whole class

- Students refine their Natural Next Questions

Actions

- Students work to answer their Natural Next Questions (e.g., original research and a summary)

- Students discuss their findings

- Students repeat steps 2-4 of the Exercise Flow

You’ll want to have the students do this exercise at least three times for them to practice improving their questions and doing research. Students can then use the research they gathered as a strong foundation for their final project or presentation.

Tips on Introducing This Exercise to Your Students:

We’ve seen the best learning outcomes happen when students are motivated and understand that this exercise is here to help them get the most value out of the project.

Here is our recommended process for introducing this exercise and getting buy-in:

- Tell a story of why this exercise matters to you personally.

- Tie it back to the students’ interests. Talk briefly about how this is the same skill they'll need throughout their lives and why they should be motivated to do this work.

- Highlight that this is new and tell the students that they are co-designers in this process and their feedback on how to improve it is critical

- Hand out the instructions and briefly describe the structure they will be going through

Building Confidence in Question-Asking:

We have observed that it takes students some time to get used to asking questions, usually two to three rounds of question-asking. Don't worry! That's normal! Make sure they understand that this is a skill to be learned just like anything else, and it's totally fine to feel its a bit difficult initially.

Next Time: How to Help Students Start Asking Questions

P.S. A little foray into the peer-reviewed literature on questions

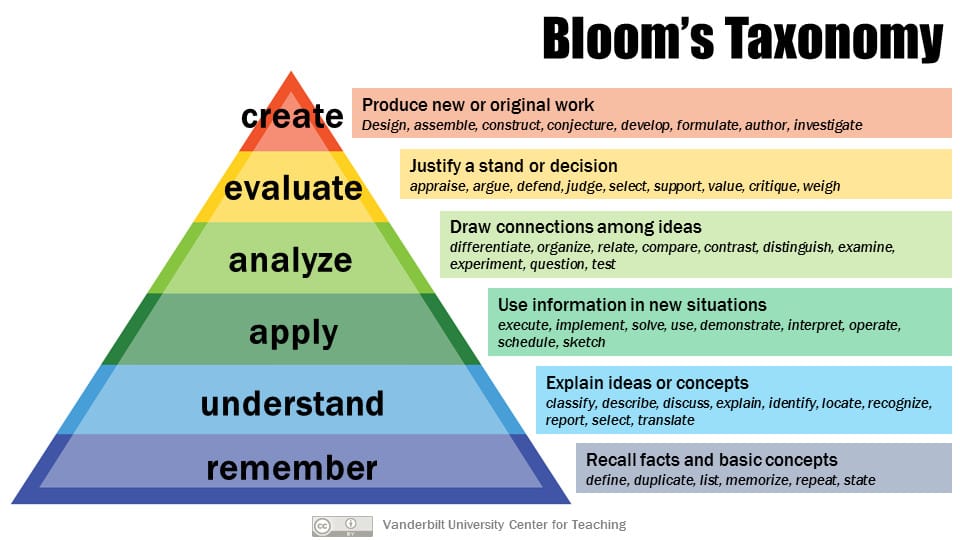

A little foray into the peer-reviewed literature on questions: Many researchers have explored the nature of questions and proposed taxonomies. Several such studies categorize student questions raised in normal classroom management (e.g., Good et al., 1987; Marbach-Ad and Sokolove, 2000), and thus do not pertain to Natural Next questions. Bloom’s taxonomy (1956) still leads the knowledge taxonomy world. Harrak et al. (2018) produced a taxonomy similar to Bloom’s, and implemented it in a computer algorithm, but this analysis did not result in a high degree of success. Similarly, Shodell (1995) and Dillon (1984) produced question taxonomies that were fundamentally simplifications of Bloom’s (Figure 1).

Researchers so far have focused primarily on the depth of comprehension of a single subject, and specifically the content knowledge of that subject. These taxonomies are useful for question-asking in response to lectures, readings, or a given class. But they don’t take learners to the Natural Next Question. Finally, you might want to read our first research results with the Question Productivity Index. Our findings will also be presented at LAK19 conference.

Figure 1: Bloom’s Knowledge Taxonomy, from Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching. The Natural Next Questions we are working with falls under “create” or extends beyond this apex.

*Hero photo created by rawpixel.com - www.freepik.com

![Are Some Questions Better Than Others? Assessing Questions with Students [Rubric Download]](/content/images/size/w100/2024/07/26661-1.jpg)